Scripture provides few details about how and exactly where Jesus was born. Nevertheless, archaeology allows us to reconstruct many of these elements, revealing something rather different from what modern Christmas art usually depicts. Excavations carried out in Bethlehem and Judea over the past centuries have uncovered numerous domestic complexes with adjoining caves and stone mangers (not wooden ones, since wood was scarce in the region). These were limestone caves. During excavation, separate storage bins or feeding troughs for animals (the mangers where straw was placed) were often carved directly into the stone. The caves were normally sealed with a small wall and door at the entrance to insulate them from the outside, or with three walls and a projecting roof if the cave was shallow. These structures served as a resting place for shepherds and local people, or as stables for animals. As one might expect, stables were built more quickly and with fewer resources, and therefore were less airtight and less comfortable.

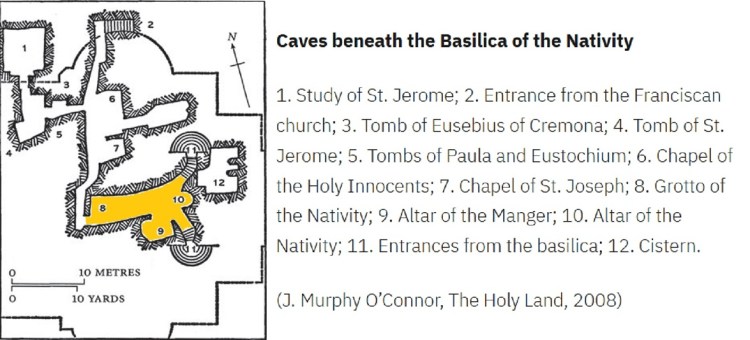

Since ancient times, a modest cave with these characteristics has been venerated in Bethlehem as the place where the Savior was born. This is the Grotto of the Nativity. If it once had projecting roofs or walls, they have not survived. The cave measures about 12.3 meters deep, 3.5 meters wide, and has an irregular ceiling that exceeds two meters at its highest points (484” x 137” x 78”). Its narrow entrance is about 1.2 meters wide (47”). Such entrances made it easier to control animals and increased protection against thieves. The interior was likely narrower originally, before thousands of Christian pilgrims took small stones as souvenirs. As soon as the Roman Empire became Christian, Constantine ordered a basilica built on the site in the fourth century, and it has been venerated continuously ever since.

Like any cave carved into limestone, this one would also have been somewhat dusty and cold, with a temperature similar during day and night. Note as well that Bethlehem is located in the highlands at about 775 meters (2,540 feet) above sea level, on a slope exposed to strong winds. We do not know with certainty on what exact day the Redeemer was born, but it must have been in late autumn or during winter. Given the lack of evidence, the most plausible approach is to follow the oldest liturgical tradition we know, dating to the early fourth century. As soon as Rome became Christian, Christmas began to be celebrated officially on December 25. In general, the visions of the saints do not contradict this date, except that of Anne Catherine Emmerich, who states that everything occurred a month earlier, on the 12th of Kislev (around November 25). If the birth occurred in November, daytime temperatures would range between 15–20°C (59–68°F) and nighttime temperatures between 5–10°C (41–50°F). If everything took place in late December, they could fall to 0°C (41°F) at night—cold enough to freeze water.

With this background, we can return to the Gospels. They first recount the anxiety of finding a suitable place for the birth, which was likely already beginning. It was a cold, windy evening after five or six days of walking. The fatigue of the journey and of labor progressively weakened the mother. The sun was setting, the evening was falling, and so was the temperature. Joseph, who was from the city of David, knew well the lodging place where travelers usually spent the night; however, after going there, he found no room available. His inquiries about shelter would have taken place at night, under the starlight and torchlight. Finally, he found a cave with a sealed entrance, probably wooden: a place someone had minimally prepared to keep animals. Upon arriving, Joseph’s cold hands would have opened the door, and the torch would have revealed an occupant in the back: a good ox taking shelter in the warmest part of the cave, next to a manger carved in stone, still with straw or dried grass. Mary, Joseph, and the donkey would have entered in that order. Inside, the wind no longer blew, and the animals provided warmth.

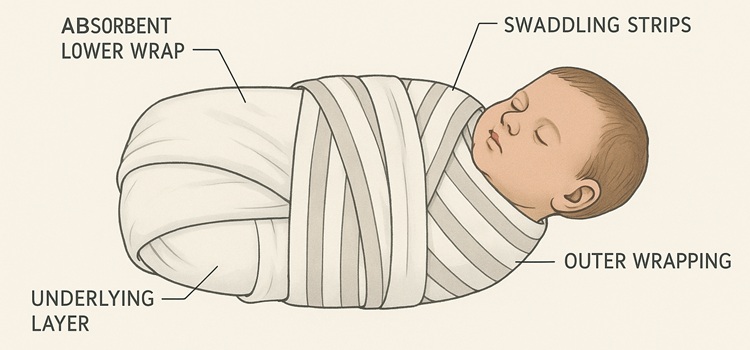

This helps us better understand what the Gospels say: Mary “gave birth to her firstborn son, wrapped him in swaddling cloths, and laid him in a manger” (Matthew 2:7; cf. Luke 2:12). The child would have been born feeling tremendous cold and would have instinctively cried out. The most urgent need in that cave was to warm him. After washing him with water, salt, and oil according to local custom, the mother hurried to literally wrap the tiny body in many, many cloths to keep him from getting cold. Only afterward would the parents adore him; only afterward would the visits and rejoicing come.

Modern Nativity paintings often show the child naked, peacefully sleeping on a white cloth that shields him from the sharp straw piled in a wooden manger. None of this follows local customs or considers the actual temperature of the place. First, the mangers were carved into limestone, often attached to the wall. Second, in first-century Mesopotamia, newborns were carefully wrapped with several layers of cloth to keep them warm, protected, and secure. A soft cloth was placed directly on the baby’s skin; then an absorbent lower band was added, serving as a primitive diaper. Over this layer, long strips of linen or wool (spargana) were applied firmly around the torso and limbs to keep the child immobile and protected from the cold. Finally, an outer wrapping reinforced the previous layers, creating a small “cocoon” that helped the baby sleep and prevented heat loss—especially in caves or cold rooms like those described in the Gospels for Jesus’s birth. Several codices and ancient paintings record these details. As we can see, God entered the world as He left it: naked and despised, with His body laid on stone, in the depths of a small-mouthed cave, wrapped entirely in linen, after having been held in His mother’s arms, washed from blood, and anointed with oil. From a cold cave He came forth, and to a cold cave He returned.

But let us return to Bethlehem, where Jesus has just been born and no longer feels the warmth of the maternal womb. The child opens His mouth, and His lungs taste the cold air for the first time. He cries. He cries from the cold! After cutting the umbilical cord and washing Him with water, salt, and oil, His parents would have wrapped Him in the swaddling cloths. This little body may still have been trembling. Mary and Joseph would arrange the straw in the manger, lay a cloth over it, and place the child there to give Him a second layer of warmth. They would then bring the torch closer, draw the animals near, and draw themselves near as well, attempting to transform this inhospitable world into a warm home. And, curiously, in that starry night and in that cold cave, this divine child at some moment managed to find peace and sleep a little, just a little.

So, everything happened just as the following carol sings:

Verse 1: Away in a manger, no crib for a bed,

The little Lord Jesus laid down His sweet head.

The stars in the sky looked down where He lay,

The little Lord Jesus, asleep on the hay.

Verse 2: The cattle are lowing, the Baby awakes,

But little Lord Jesus, no crying He makes;

I love Thee, Lord Jesus, look down from the sky

And stay by my cradle till morning is nigh.

Verse 3: Be near me, Lord Jesus, I ask Thee to stay

Close by me forever, and love me, I pray;

Bless all the dear children in Thy tender care,

And fit us for Heaven to live with Thee there.

Merry Christmas!

Juan Carlos Riofrío

Washington, D.C., December 24th, 2025

2 comentarios sobre “Archaeology on the Cave of Bethlehem and the Swaddling Cloths of Jesus”